Dan Crenshaw, or as he's aptly known in gun rights circles, "Fuddshaw," is apparently on a copy/paste campaign defending the GOP's capitulation to the Communist left. Crenshaw accused other Republicans, specifically Senators Cruz and Hawley, of lying to millions. The legislature of the United States has no part to play, constitutionally, in deciding the outcome of this election according to Dan.

And he'd be right in saying that there's nothing in the Constitution that delineates what Congress is to do under those circumstances. But I'm afraid it's not so simple as arguing that omission necessitates accepting a fraudulent election.

One thing that struck me during this entire ordeal was the use of the word "unprecedented." I kept hearing opponents of objections to the certification use that word, for the blatant purpose of absolving themselves of any obligation, or even ability to address the issue. Some of you may have heard the election of 1820 broached during all of this. Here's why. Missouri was in the process of becoming a state when the election of 1820 transpired (November). The United States Congress passed a law the previous March instructing Missouri to form a government in conformity with the U.S. Constitution, upon which it would be admitted into the Union as an equal member.

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America, in Congress assembled, That the inhabitants of that portion of the Missouri territory included within the boundaries herein after designated, be, and they are hereby, authorized to form for themselves a constitution and state government, and to assume such name as they shall deem proper; and the said state, when formed, shall be admitted into the Union, upon an equal footing with the original states, in all respects whatsoever. - An Act to authorize the people of the Missouri territory to form a constitution and state government, and for the admission of such state into the Union on an equal footing with the original states, and to prohibit slavery in certain territories, March 6, 1820.

This would naturally confer upon Missouri, like every other state, the right to appoint presidential electors. A dispute arose over whether or not Missouri had met all the obligations of the Act at the time of the election however, and whether or not its votes should be counted. Some were in favor of including them and others were opposed. Ultimately the legislature decided not to address the matter at the time, because the votes of Missouri would have been nugatory to the outcome. Incumbent James Monroe had won every state then in the Union, and every elector save one, who voted for Adams. What's perhaps more important, is that some in Congress acknowledged that this incident exposed a Constitutional deficiency, referring to it as a casus omissus (a gap in the law), and even argued it should be addressed contemporaneously to prevent future controversy.

"Mr. C. (Henry Clay) said there was no mode pointed out in the Constitution of settling litigated questions arising in the discharge of this duty; it was a casus omissus; and he thought it would be proper, either by some act of derivative legislation, or by an amendment of the Constitution itself, to supply the defect."

"Mr. (James) Barbour said that, on the present occasion, as the election could not be affected by the votes of any one state, no difficulty could arise; and that it was his intention hereafter to bring the subject up, to remedy what he considered a casus omissus in the Constitution, either by an act of Congress, if that should appear sufficient, or, if not, by proposing an amendment to the Constitution itself."

"In the original plan, as well as in the amendment, no provision is made for the discussion or decision of any questions, which may arise, as to the regularity and authenticity of the returns of the electoral votes, or the right of the persons, who gave the votes, or the manner, or circumstances, in which they ought to be counted. It seems to have been taken for granted, that no question could ever arise on the subject; and that nothing more was necessary, than to open the certificates, which were produced, in the presence of both houses, and to count the names and numbers, as returned. Yet it is easily to be conceived, that very delicate and interesting inquiries may occur, fit to be debated and decided by some deliberative body. In fact, a question did occur upon the counting of the votes for the presidency in 1821 upon the re-election of Mr. Monroe, whether the votes of the state of Missouri could be counted; but as the count would make no difference in the choice, and the declaration was made of his re-election, the senate immediately withdrew; and the jurisdiction, as well as the course of proceeding in a case of real controversy, was left in a most embarrassing situation." - Commentaries on the Constitution of The United States, 1833.

Why am I pointing this out? To illustrate something. Despite what you're being told by your representatives, challenging the votes of presidential electors is not "unprecedented," and they do have the means to remedy the "defect." They've simply chosen not to. The Congress proposed no legislation, no Constitutional Amendment to that end, despite knowing this crisis was imminent for weeks in advance. Instead they conspired to band together in dereliction. When the time comes we will cite precedent, or lack thereof, as an excuse to do nothing. The Democrats used the "casus omissus in the Constitution" to sustain a fraudulent election, and the GOP establishment used it to justify capitulation to the Democrats.

Time has proven Representative William Trimble's sentiments on the matter incredibly sagacious, and indeed, made of them prognostication. Stating their course of action would be:

"Cited hereafter as precedent; and precedents were becoming important things in the public transactions. The House might set an example by this vote, as ruinous in its consequences, as any decision which could be made."

He could not have been more correct, as the 116th Congress did the same thing when confronted with this problem, as the 16th Congress. Nothing. Like the 16th Congress, they not only didn't use any discretion in addressing the matter, they also didn't correct the defect. But unlike the 16th Congress, they don't have the excuse of it being a new/unforeseen problem, and the consequences of their apathy have far greater ramifications. The votes of Missouri would not have changed the outcome of the election of 1820. But in this election the outcome was at stake.

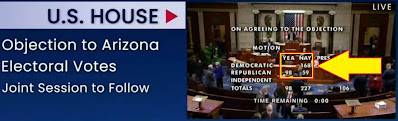

The GOP establishment seems to want you to believe that by choosing to do nothing they took no side. That they were merely hapless bystanders. But that's not true. Scores of Republicans chose Joe Biden by voting against objections to the result of the election by multiple states. They chose Joe Biden by ignoring the electors appointed by multiple state legislatures.

"It is observable, that the language of the constitution is, that 'each state shall appoint in such manner, as the legislature thereof may direct,' the number of electors, to which the state is entitled. Under this authority the appointment of electors has been variously provided for by the state legislatures. In some states the legislature have directly chosen the electors themselves; in others they have been chosen by the people by a general ticket throughout the whole state; and in others by the people in electoral districts, fixed by the legislature, a certain number of electors being apportioned to each district. No question has ever arisen, as to the constitutionality of either mode, except that of a direct choice by the legislature. But this, though often doubted by able and ingenious minds, has been firmly established in practice, ever since the adoption of the Constitution." - Commentaries on the Constitution of The United States, 1833.

Several states appointed alternate electors, in response to what they believed was significant voter fraud in their states, and your representatives at the Capitol simply chose to ignore them and certify Joe Biden. That's not inaction. Republican lawmakers used the precedent of inaction to justify doing nothing, but disregarded that this as an issue the Congress can, and should address.

I've broached the topics of federalism, of federal encroachment upon state sovereignty and autonomy, etc., before. And I've illustrated how, in the event that state governments fail to protect the liberties of their citizens, it falls to the federal government to assume that responsibility. And this in my opinion lies at the crux of this issue as well. I have no interest in the federal government nullifying the result of state elections. But what is to be done in the event that states using compromised voting systems render illegitimate election results, and appeals to those state governments by their citizens are ineffectual? Our representatives love to laud the virtues of democracy, and purport to be proponents of it, but what is democratic about a handful of (battleground) states determining the outcome of elections for the entire Union? Particularly when those states are suspected of engaging in fraud?

What the GOP establishment essentially told us on the 6th, is that in the interest of preserving state's rights, it's standing aside as the party that's been working for generations to establish unfettered federal supremacy assumes control of the federal government. That for the purpose of adhering to the Constitution, it's surrendering the federal government to two people that have openly expressed their intent to ban guns unconstitutionally through executive decree, for example.

Thankfully, guys like Dan took a stand against despotic federal usurpation on the 6th, by facilitating the elevation to power of two people hellbent on exercising despotic federal usurpation. But Dan can sleep sound at night knowing he adhered to the Constitution, when he stepped aside to hand over power to a party that won't.